October 29, 2024: Theatre Yesterday and Today, by Ron Fassler

As a teenager and developing theatre nerd of the 1960s, it was always fun to open the theatre section of the New York Times and see a small ad offering some variation on the line: “What? You haven’t seen Man of La Mancha once?” It was clever and, not for nothing, the show's co-producer Hal James had spent the bulk of his career in advertising.

It’s hard to imagine producers today taking the risks that James and Albert W. Selden did in 1965 when they commissioned a musical based on Spanish writer Miguel de Cervantes’s 17th century novel, Don Quixote. Actually two books, with its first part published in 1605 followed by its second in 1616, it is largely believed to be the first modern novel in Western literature.

Selden had a big hand in the 1963 restoration of the Goodspeed Opera House in East Haddam, Connecticut, that sits on a bluff overlooking the Connecticut River about a hundred miles north of Manhattan. The structure was first built in 1877 and has undergone numerous owners and transformations throughout its history. If you can believe it, during World War II, it was purchased by the State Highway Department and used for the storage of winter-maintenance equipment. In 1959, the stage of Connecticut condemned the structure and a group of concerned citizens were able to buy it at the cost of $1 and raise the funds necessary to create what is still today a jewel box of a theatre. Seating only 398, this is where Man of La Mancha had its premiere in 1965, hoping for it to serve as a pre-Broadway tryout. It became the first of nineteen musicals that would eventually find their way to Broadway (Shenandoah and Annie among the most successful of them). La Mancha boasted a first class production staged by Albert Marre, as well as a central performance from Richard Kiley that gave the versatile actor the role for which he would be identified for the rest of his life.

However, Man of La Mancha’s route to Broadway was a circuitous one, mainly due to no one wanting to give it a home. East Haddam isn’t Broadway and the major theatre owners of the day weren’t persuaded it was anything special. So instead, Selden and James opened it off-Broadway at the recently built ANTA-Washington Square Theatre in Greenwich Village next to NYU and Washington Square Park. Erected quickly and efficiently a year earlier, the 1,100-seat space was built from scratch on land leased for $1 a year (there’s that special price again) by NYU to the non-profit company as a temporary spot for the Lincoln Center Theatre Company. This was because its permanent home, the Vivian Beaumont Theatre on the campus of its brand new West Side complex, hadn’t been completed yet. Universally applauded for its thrust stage, with audiences surrounding it in a three-quarter configuration, it was designed by Jo Mielziner, one of the pioneering scenic designers of his time, who was also in charge of the Beaumont.

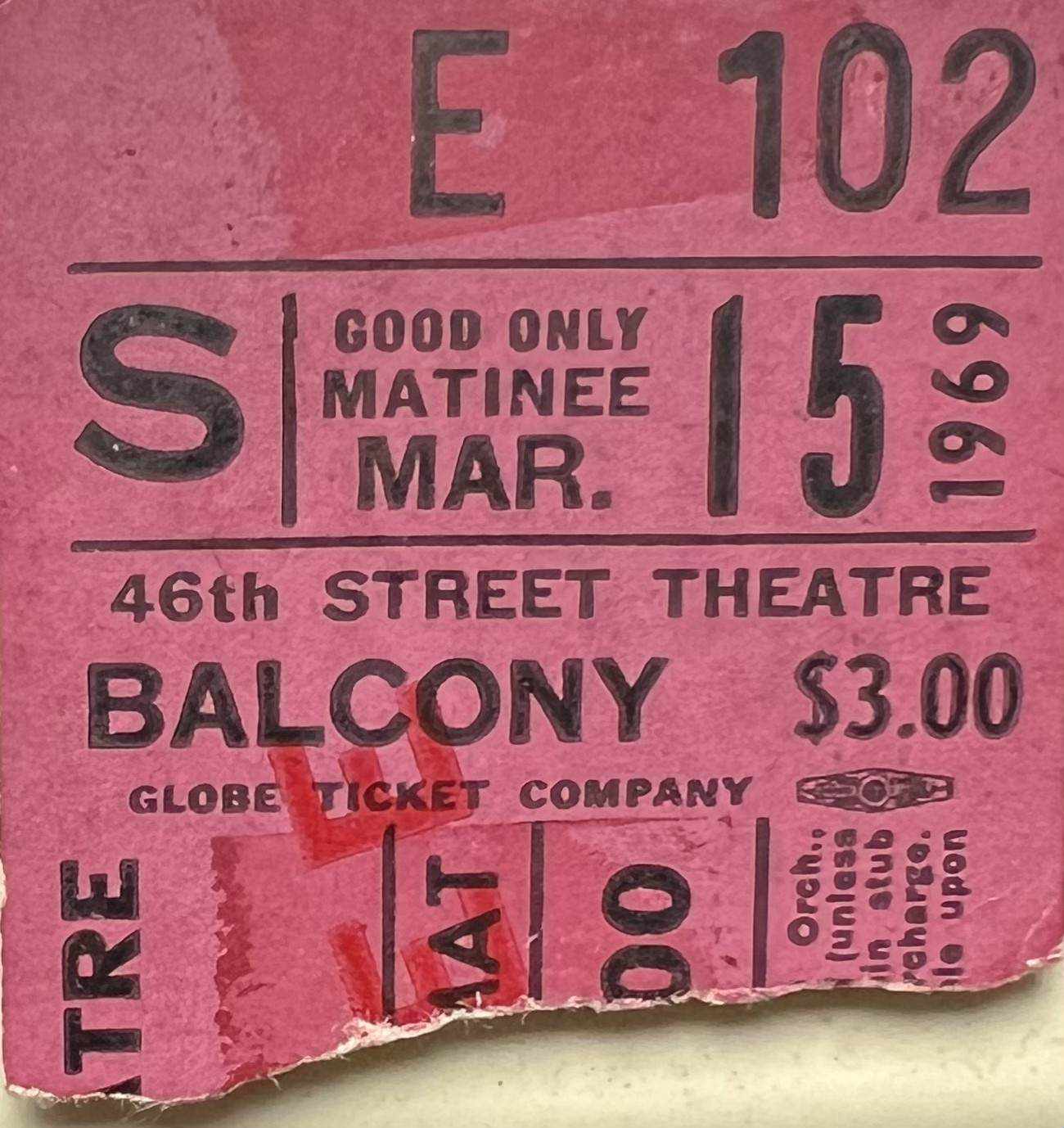

After about five weeks, with word-of-mouth building, Man of La Mancha became a sellout downtown with scalpers getting $100 ($800 in today’s dollars). Over the course of its nearly six-year run, it ended up in four theatres: Beginning off-Broadway, it then moved to Broadway, then back downtown again off-Broadway, then finally closing uptown on Broadway where, at age fourteen, I was present at its 2,328th and final performance (it was my fifth time seeing it).

Its success went against all odds. Dark and often downbeat for a musical—this was years before Les Misérables—its secret sauce was in the genuine emotion it put forth by its succession of beautiful ballads by composer Mitch Leigh and lyricist Joe Darion, even if they may not have been to everyone’s taste (Life Magazine wrote, “The music actually veers towards the banal, but Illusion makes it sound better”). “The Quest,” as it is listed in the show’s song list, became the very definition of something written for a Broadway musical that went on to become a standard. Better known as “The Impossible Dream,” its familiarity to the general public was used it in every conceivable fashion to advertise the show.

There had been numerous attempts to put Don Quixote on stage and film prior to Man of La Mancha, but the sheer size of the work daunted a number of prior writers (there are more than four hundred characters in the two novels). But playwright Dale Wasserman had actually cracked it in an initial attempt at dramatizing it a few years earlier when, for a television production, he used the exact same concept for the musical of a play-within-a-play. I, Don Quixote aired live for one night only in 1959 in a ninety-minute production on CBS as part of The DuPont Show of the Month. It starred Lee J. Cobb as Cervantes/Don Quixote, Colleen Dewhurst as Aldonza, (making her television debut) and Eli Wallach as Sancho Panza. Its sole copy exists at the Library at Lincoln Center and upon viewing it there, I came away amazed at the striking similarities between it and Man of La Mancha.

Seen by twenty million people at the time, it won Wasserman a Writer’s Guild Award. It’s pretty damn good, especially when you take in the vagaries of live television. Cobb and Wallach ride real animals in a few scenes which resulted in bruises (no broken bones) when Cobb fell off his horse during rehearsal. The final results went more smoothly. Cobb used his mellifluous voice expertly; Wallach mined all the comedic juice out of Sancho, and Dewhurst dazzled in her usual radiant way, even more so seeing her emanate with such a youthful glow. As the credits rolled on this Dupont Show of the Week, I noticed the credit for the stage manager as one Joseph Papirofsky, who would change his name and be later known as the fearless theatre producer, Joseph Papp.

In turning the property into a musical, Leigh and Darion did what most good theatre writers do: steal everything they could from Wasserman’s libretto. This included taking the words Quixote offers Aldonza of how he must “dream the impossible dream, to fight the unbeatable foe” and putting them to fine use.

Whenever business on Broadway would slow down, a new star would be brought in to pep up sales. Troves of actors played the role—by my count fifteen of them in the course of its six-year run—though some only played for a couple of weeks. Succeeding Richard Kiley were Jose Ferrer (Cyrano de Bergerac), Hal Holbrook (Mark Twain Tonight) and Lloyd Bridges (famous for his TV series Sea Hunt in which he was called upon to spend a great deal of the time underwater). John Cullum, not as well-known as he would later become, also lent his strong voice to the part, as did Laurence Guittard, the first actor promoted from standby to playing all matinee performances. Twenty-four years old at the time, a decade later he would create the role of Count Carl-Magnus in A Little Night Music.

During its time on Broadway, international productions of Man of La Mancha were simultaneously playing to wide audiences in every corner of the globe. So, in a burst of creative producing, “The Festival of International Don Quixotes” was born. Brought in from afar were Mexican actor Claudio Brook, who was among the cast of Luis Buñuel’s much lauded 1962 film The Exterminating Angel, Charles West of the Australian production of La Mancha, and Gideon Singer from Israel. Many appreciated Keith Michell's Don Quixote, an Australian-born actor who spent the bulk of his career in the United Kingdom for much of his career. You can hear him on the London cast album of the show when he played it on the West End in 1968 opposite the show's original Aldonza, Joan Diener (near complete on a two-record set with much of the book included).

The international experiment was especially tricky when Japanese actor Somegoro Ichikawa, who originated the role in Tokyo, came to Broadway. “The marvel is that he didn’t speak a word of English but memorized the lines phonetically,” said Dale Wasserman, astounded by the twenty-seven-year-old actor’s commitment. Of his own challenges, Somegoro told the New York Time, “As the actor Somegoro, I feel as if I were confronting the same kind of tremendous barriers that the character Don Quixote did. And I have no weapons other than this.”

As Somegoro further stated, he found many “striking parallels between the techniques used in La Mancha and those of Kabuki . . . the shifting back and forth of time and space, for instance, all on the same stage. The quick changes of costume as the actor alternates from Cervantes, and his creation Don Quixote. The use of songs, dance and declamation. The use of actors on stage as prop men. Kabuki is old, La Mancha is new.”

Rumor has it that Hugh Jackman currently has his eyes on the musical for a potential revival (Brian Stokes Mitchell played it last in 2002, so twenty years makes the time ripe once again). As a high school student, Jackman vividly remembered seeing Man of La Mancha, telling Playbill in a 2019 article, “I can replay it like a film in my head; I was mesmerized. That’s probably where the spark came from that made me want to do it for the rest of my life.”

Or, as Quixote so gloriously sings, “My destiny calls and I go.”

Ron Fassler is the author of Up in the Cheap Seats: An Historical Memoir of Broadway and the forthcoming The Show Goes On: Broadway Hirings, Firings and Replacements. For news and "Theatre Yesterday and Today" columns when they break, please hit the FOLLOW button.

Write a comment ...