January 4, 2025: Theatre Yesterday and Today, by Ron Fassler

When an actor is involved in something they want to get out of, they can get out of it. Even though legally binding contracts are signed they all can be broken. Of course, no one wants to be labeled a problem actor or someone who can’t be trusted, which leads to performing under duress. This sort of unhappiness absolutely colors what occurs onstage or in front of a camera with the results sadly resembling a hostage situation. Either an actor takes the situation out on themselves or they take it out on others. If the only way out is to get fired, being creative comes naturally to them. After all, using their imaginations is how an actor makes a living.

One such theatre story involves a world famous actress who was starring on Broadway in something that was making her desperately unhappy. The complication was that she was also the de facto producer of the show which took the option of quitting off the table since not only would her exit put an entire company out of work, but it would literally take money out of her own pocket. This was the complicated dilemma faced by Lucille Ball in 1960 when she chose to take the plunge and star in Wildcat, her one and only Broadway musical.

This marked the belated Broadway debut at age forty-nine of the beloved television icon and it was an open secret that she provided the funding for the entire production. Though the Playbill had the names Michael Kidd and N. Richard Nash, its respective director and author, as the over-the-title producers, Ball herself was the musical’s muscle. It said as much at the very bottom of the program’s title page: “THE PRODUCERS ACKNOWLEDGE THEIR THANKS TO DESILU PRODUCTIONS, INC. FOR ITS COOPERATION.”

Trust me, the entire world knew what Desilu was.

John McClain of the Journal American even took note of it in his opening night review: “The rich get richer, and a redhaired millionairess named Lucille Ball figures to make another bundle with a new musical, Wildcat, in which she is the star and sole backer.”

Well, that prediction did not come true. Yes, the show’s box office kept up in spite of unenthusiastic reviews but overall it left Ball with the miserable feeling she was letting her fans down eight times a week. Richard Watts in the New York Post called Wildcat “a tremendous disappointment,” though praised the Cy Coleman-Carolyn Leigh score as “bright and pleasant” (which it is). It actually produced a hit song, “Hey, Look Me Over,” recorded throughout the 1960s by Louis Armstrong, Rosemary Clooney, Bing Crosby, Judy Garland, Peggy Lee, Johnny Mathis and Mel Tormé, among others.

And about that song... it presented a predicament, as composer Cy Coleman once told a reporter: “How do you write for a woman who had five good notes? And not just any woman, but the biggest star in the world at the time. What is she going to sing when she steps out on that stage for the first time? She had to land big or else we were all dead.” Happily, they figured it out.

If you care to give a listen and a look to “Hey, Look Me Over,” here’s Ball and Paula Stewart, who played her younger sister in Wildcat, belting it out for the world to hear on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1961 (“Lucille Ball, I’d probably say you are the most beloved star in show business”):

The problem with Wildcat was N. Richard Nash’s tedious book. Substituting dry oil wells for dry farmland amounted to nothing more than a watered down version of his far better 1954 play The Rainmaker. It spite of some rousing numbers, it didn’t come together to anyone’s satisfaction, including the show’s inventive director/choreographer Michael Kidd. “Lucille Ball finally made it to Broadway Friday night, dragging along the book of the musical Wildcat,” was the opening line of critic Ward Morehouse’s review, which pretty much summed up the feelings of both critics and audiences.

But the advance sale was enormous, what with Ball’s status as the most famous woman on all of television, so the box office was strong. Having just ended the Lucy-Desi Comedy Hour earlier in the year, that show had followed on the heels of 180 episodes of I Love Lucy, still in syndication more than seventy years later. At its peak, I Love Lucy was seen by 60% of all households in America. For practically the entire 1950s, she and her husband Desi Arnaz were the biggest stars on all of television. Ball’s popularity was so great that Wildcat’s audiences didn’t seem to mind its banality.

However, having signed onto an eighteen-month contract, she was now stuck in something she got little satisfaction from doing. But she didn't shirk her duties. As Ken Mandelbaum writes in his book Not Since Carrie: 40 Years of Broadway Musical Flops (1991): “[Wildcat] opened to strong business [and] there can be little doubt that it would have gone on to run for the duration of Ball’s contract and return its investment. Ball had worked hard through rehearsals and the Philadelphia break-in, and she was still committed to the show when it arrived in New York, adding a ‘third act’ curtain call in which she spoke to the audience, dance, and did an encore of ‘Hey, Look Me Over.’”

But the devastation of Ball’s divorce from Arnaz being finalized during the musical’s run exacerbated a number of existing health issues. She wound up dropping two of her six songs to help combat exhaustion and eventually put the show on pause to take two weeks off and recuperate in Miami. Upon her return, Ball may have felt better physically, but her heart wasn’t in it. In May, during the show’s 5th month, she slipped onstage during a performance, her fall broken by cast member Edith King, which resulted in the fracturing of her own wrist. Ball’s understudy, Betty Jane Watson, finished the performance and went on for the rest of the week, followed by an announcement that there would be an eight to nine-week hiatus to allow its star the rest required before returning.

But she never came back. As the show’s sole investor, Ball had the power to shut it down and she did before it completed six months on Broadway. Desilu Productions had financed its $300,000 (some reports say $400,000) budget and it was her call to close Wildcat even though it was still selling well. Ball had to return $165,000 to those who purchased tickets. Very rich and very much a perfectionist, she probably had few regrets.

In looking back on Wildcat, Ball said, “Nobody told me how bad it was. Except the gypsies in the chorus. They knew everything.”

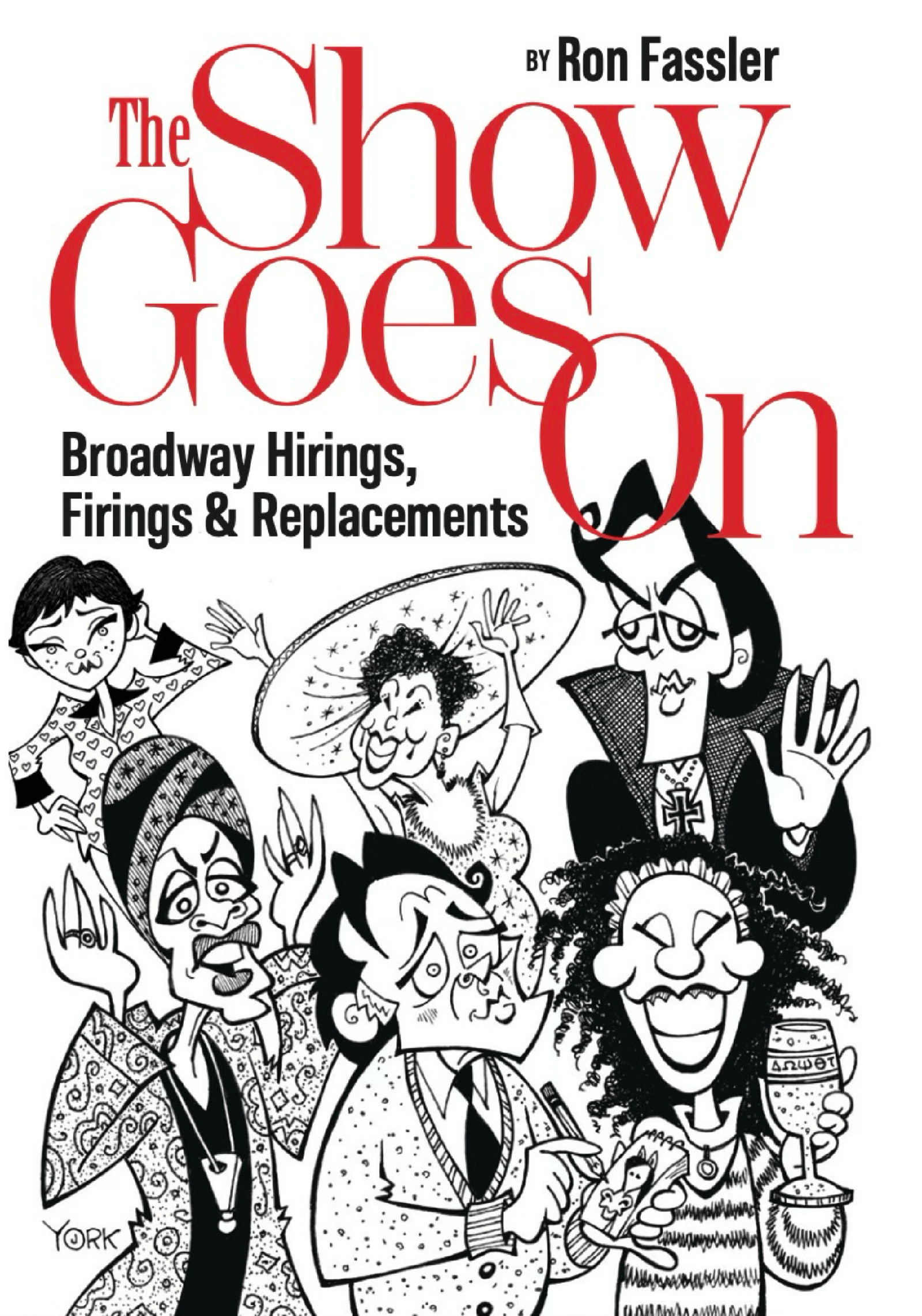

Ron Fassler is the author of the recently published The Show Goes On: Broadway Hirings, Firings and Replacements. For news and "Theatre Yesterday and Today" columns when they break, please hit the FOLLOW button.

Write a comment ...