“For me, my background is poetry, and that’s the foundation on which I approach my plays: the sound of the word, the idea of taking concepts and pressing them into 14 or 22 lines and making a whole, complete statement about something.” - August Wilson, 1987

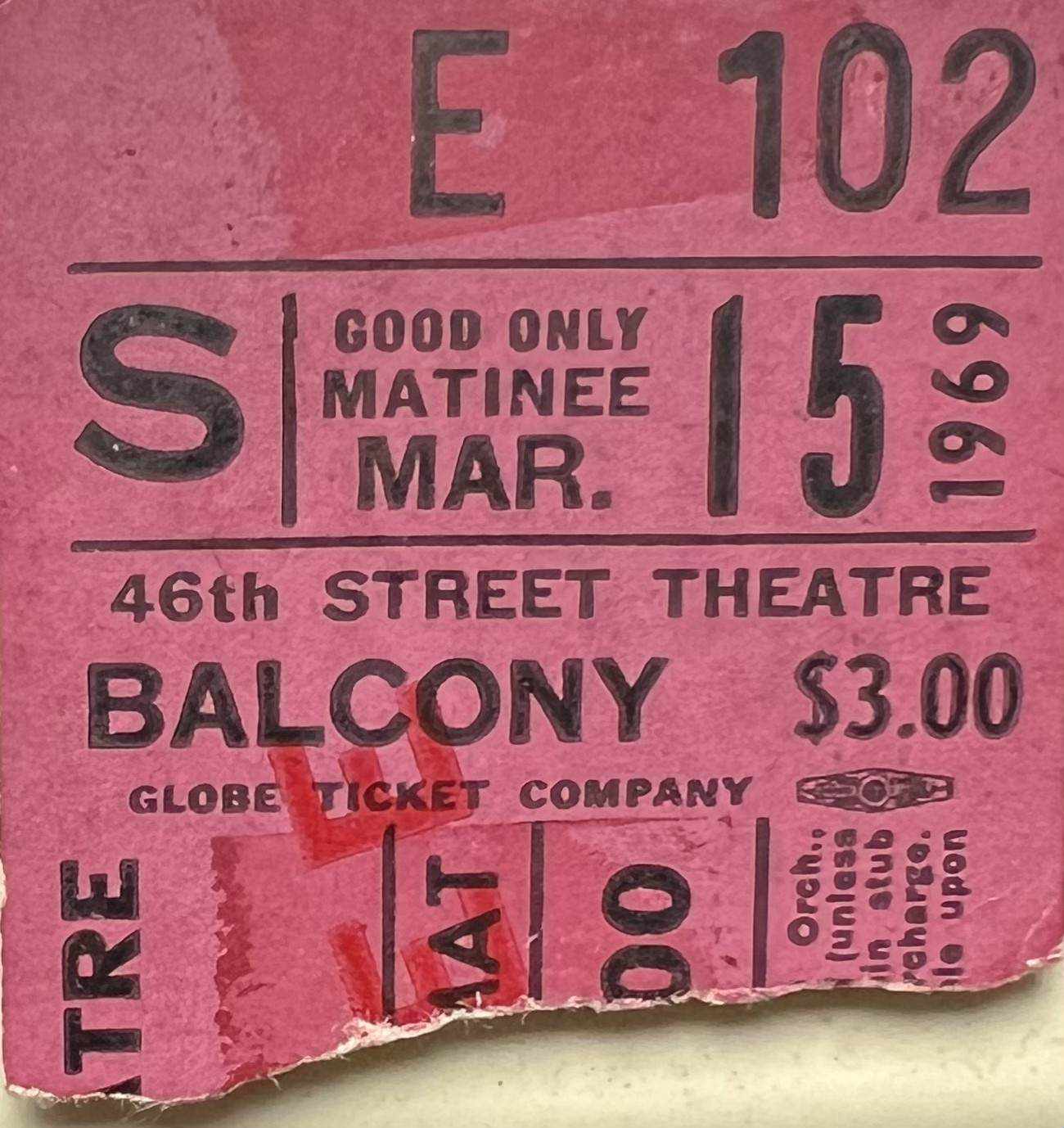

Of all the playwrights whose dramas probe the human condition, there is no one who expressed themselves in a more poetic fashion, or whose work I admire more, than August Wilson (1945-2005). And how strange is that, really? Our backgrounds couldn't be more different and the people about whom he wrote in his ten plays — the American Cycle, as they have come to be known — don't spring from any personal experience of my own. And yet, he's the most profound and important playwright who came of age in my lifetime. I consider myself fortunate to have had the opportunity of seeing a number of his plays in their original Broadway incarnations over the years, as well as excellent regional theatre productions. In fact, one of the very last plays I attended before theatre was halted in March, was his final play, Radio Golf, at the Two River Theatre in Red Bank, a New Jersey company dedicated to doing every one of the American Cycle (they have five to go).

In 1984, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom was the first play of Wilson's to open on Broadway and, in the intervening thirty-six years, only the second to be made into a motion picture. The film of his 1987 Tony Award and Pulitzer Prize winning Fences came out in 2016, grossing an impressive $64 million against a $24 million production budget and winning Viola Davis a much-deserved Academy Award. Now with Ma Rainey's strong reviews and impressive early numbers in Netflix viewership, Wilson's work is poised to be seen by its most massive audience to date — courtesy of the streaming service that has transformed the way the world gets its movies. That's not only due to the effects of Covid-19 on the film distribution business, but because of the exquisite vision of director George C. Wolfe as well as the stripped-down adaptation by Ruben Santiago-Hudson, a longtime interpreter of Wilson's work both as actor and director. What they have provided is a tight, visual means to allow Wilson's writing to soar: an impassioned discourse of a vitally contemporary subject, while set nearly a century ago.

Since the film of Fences came out in 2016, we have had the Black Lives Matter movement take hold across the country, bringing a stronger sense of awareness to how deep systemic racism goes. We live in incendiary times, though it is with great hope that with a new government about to be sent to Washington — one with the opposite intent of what's been instituted over the past four years — guarded optimism may be in the air. And though some might scoff at Ma Rainey as being an entertainment, there is still the chance for minds to be opened after seeing it, especially due to the double impact of viewing the tragedy which befalls the character of Levee in Chadwick Boseman's heartbreaking performance. The fact that the actor knew he was dying of terminal cancer while filming, and even showed up for additional re-recording of his dialogue just four weeks before he succumbed, imbues his work here with both uplift and dread. To call it merely powerful is to undermine how it seeps into the consciousness of anyone viewing it.

Ma Rainey's Black Bottom appropriates a real-life character in a somewhat fictional story. In Wilson's telling, "Mother of the Blues" Ma Rainey arrives in a Chicago recording studio in 1927 to set down some of her most popular songs to vinyl. Though renowned in the Deep South, records were still in their infancy, thus the importance of this session to help increase her popularity to the North, though just how remunerative that would be for Ma or other people of color in the music industry was a serious issue. Over the ensuing decades, many were cheated and swindled by having their music misappropriated and handed over to white musicians. Wilson supplies Ma with a small band of characters who accompany her to Chicago: Slow Drag (bass), Toledo (piano) and Cutler (trombone) being the tried and true of the group. But it's Levee, a young trumpet player who writes his own songs, who has both the imagination and determination to bust out on his own. Tragically, he also has enough anger in him to fuel a furnace, and it is his story intertwined with Ma's that brings the drama to its surprise conclusion.

The play works beautifully on stage, set as it is solely in the recording studio. The film wisely shifts the rehearsals to another space in the basement, allowing for distance and for cross cutting that add to the tension. There is also a short prologue and a strikingly conceived coda, both musical. Of the former, the opening image is that of two young Black men running through the woods at night. Lit only by the moon, leaves and sticks crunch under their feet to the accompaniment of dogs barking. Naturally, it conjures up a very specific and scary image. But all is quickly upended when we discover that they aren't running from something, but towards something — a tent where Ma Rainey is boisterously and joyously performing.

"I wanted to start the film with everybody's pre-conceived notion of what the South is," director George C. Wolfe recently told WNYC radio's All of It broadcast. "Everybody thinks that if there's a black person in the South in 1927 that they're running from the Klan. And as much as the horror of that, and Jim Crow laws, and lynching were going on, people had businesses and careers and there was a community that supported itself... everybody is running towards a possibility, instead of what you think you know about the South. So, I thought by disrupting that — by first exposing people's expectations of anytime they see two black men running — that by disrupting that, it would make them available for the next moment, which is just at the point where Ma Rainey is entertaining, shattering along the way what you think you know, so you can be available for what is happening inside of the story."

I won't reveal the coda (though I'm tempted). What Santiago-Hudson and Wolfe do is bold and brilliant; turning something suggested in the text into something literal, the image of which exposes the dark underbelly of racism in a decimating light. And I would also be remiss if in addition to Boseman and David, I didn't mention the sterling performances given by the entire ensemble, which include Colman Domingo, Glynn Turman, Michael Potts, Jeremy Shamos, Jonny Coyne, Taylor Paige and Dusan Brown.

The commitment to film all of Wilson's ten plays is the passion project of Denzel Washington, who won a Tony for his performance in the 2010 Broadway revival of Fences. He is the producer of Ma Rainey and my imagination has run wild wondering what roles he might take on in some of the adaptations that are to come. Though there has been no announcement or, for all I know, any discussion, look for him to play the title character in Wilson’s King Hedley II, a part tailor-made to his special gifts if there ever was one.

Statistically speaking, nine of the ten in Wilson's American Cycle earned Tony Award nominations for Best Play (the tenth, Jitney, was ineligible due to its having had its premiere off-Broadway instead of on). The first written, Jitney did finally arrive on Broadway in 2017 winning a well-deserved Tony for Best Revival (giving Wilson a posthumous one to add to his previous win for Fences). And of the ten plays, eight of the nine that were eligible won the New York Drama Critics' Circle for Best Play. Will any playwright ever achieve that distinction again? In 2005 when the Jujamcyn Organization renamed the former Virginia Theatre on West 52nd Street for Wilson it was not some symbolic gesture. Coming as it did just two weeks after his untimely passing at age sixty, it may have felt sympathetic (which it was), but it was also truly earned.

A more detailed column I wrote four years ago on the life and career of August Wilson is available here. It's clear my admiration for his work knows no bounds and it thrills me that Ma Rainey has turned out to be as compelling and as well received as it has. Even after his death fifteen years ago, there is a guarantee of more interpretations of Wilson's major works over the next fifteen or so, and for that there is no cause to sing the blues.

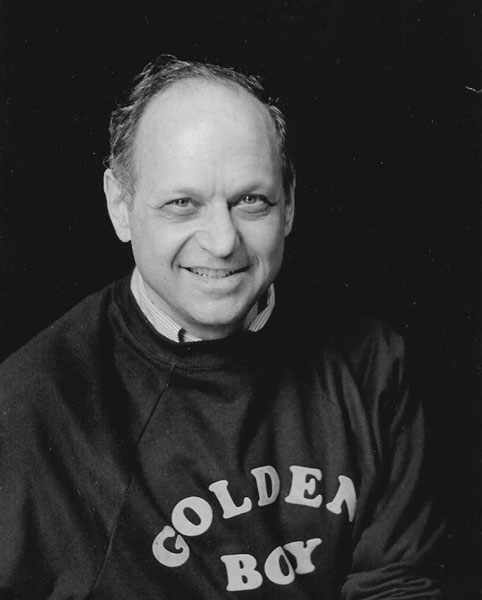

If you enjoy these columns, check out Up in the Cheap Seats: A Historical Memoir of Broadway, available at Amazon.com in hardcover, softcover and e-book. And please feel free to email me with comments or questions at Ron@ronfassler.org.

Write a comment ...