Today marks the 124th birthday of the actress/singer/dancer Ethel Shutta (pronounced Shuh-tay), born in 1896, and immortalized as the person who introduced the Stephen Sondheim favorite “Broadway Baby,” in the 1971 musical Follies. She was seventy-four-years-old on its opening night; the oldest member of the company. Enjoy this stroll down memory lane in today's "Theatre Yesterday and Today."

By age seventy-four, Ethel Shutta had experienced a long up-and-down career in show business that began when she was a child in vaudeville, carried on through radio; on Broadway in The Ziegfeld Follies of 1925 and later opposite Eddie Cantor in Whoopee! (a role she recreated in the film version); and culminating with her swan song (literally) in the aforementioned Follies, James Goldman and Stephen Sondheim's musical about a theatre being demolished and its "first and last reunion" on its stage before "in a burst of glory, it's be a parking lot." For all involved it was clear from the first day of rehearsal on Follies that the match of singer to song was perfection personified. And even though “Broadway Baby” was never designed as a true solo, but part of a trio of songs with Shutta’s originally set as the middle one, the audience response was so strong from the get-go that a change needed to be made. Fifi D’Orsay singing “Ah, Paris!” had to be moved to the middle spot so the montage would finish with the appropriate build and close out with "Broadway Baby." Shutta once told a friend of mine that “Fifi never got over that.”

Ted Chapin’s wonderful memoir, Everything Was Possible: The Birth of the Musical Follies, is a chronicle told from his vantage point as a college-aged “gofer” on the original production. In it, he reports how when auditioning actors for the show, Harold Prince and Joanna Merlin (its director and casting director) were focused on finding anyone with a connection to the heyday of the the Ziegfeld Follies. In Shutta’s case they were handed a gift, as she was the one holdover from a previous incarnation of the show that was, at one time, to be produced by Stuart Ostrow (1776, Pippin). Not one to take anything for granted, Chapin tells of how Shutta wrote Joanna Merlin a four-page thank you letter, which stated how happy she was to be cast because she thought her career was over.

It’s one of the reasons why her “Broadway Baby” works on so many levels. Ostensibly, it’s a song this old lady once sang as a young chanteuse with all its youthful optimism now colored by all that came between her twenties and seventies. Shutta was totally in on the joke, but there was something about the way she sold it that still held onto a youthful optimism while also filling it with a wry cynicism. Shutta was one of those types who loved being on stage so much that she never wanted to stop working. This was true when her career was put on hold for a while during a time she struggled with a drinking problem, but she fought back. Her fingernails always clung to the ledge of show business until her dying day, working a tiny role on the daytime soap Ryan’s Hope (which is not credited to her page on IMDB, unfortunately — an oversight I’m sure she would have hated).

As sensational as she is when you hear her on the recording of Follies, unless you saw her performing it, you really can't imagine what she was doing while she sang “Broadway Baby.” No such problem for me as I was lucky enough to see Follies as a fourteen-year-old at the April 3, 1971 Saturday matinee prior to its Sunday night opening. In the review I committed to paper when I came home from the show, I wrote: "Ethel Shutta brings down the house with her one song." Genuine critics wrote the same thing the very next day.

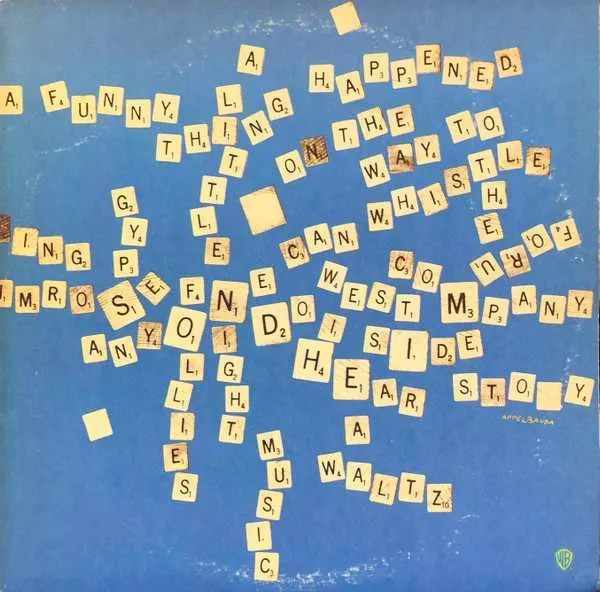

Shutta stayed with Follies for its entire fifteen-month Broadway run and recreated her role in the Los Angeles production in the late summer of 1972 with members of the original cast. It turned out to be a shorter run than anyone anticipated, as due to poor business, it ended early and didn't tour as it was planned. But there was one last performance of “Broadway Baby” left for Ethel Shutta to give, which came as a gift in the form of a chance to sing it one more time at the age of seventy-six. This was at the 1973 "Sondheim Tribute,” thankfully recorded live as a double-record-set, known to aficionados as the “Scrabble Album.” And seriously, it could drive a person crazy trying to decipher what the hell Shutta is doing to solicit screams of laughter from the audience. And her ovation does just what I said it did at the matinee two years prior at which I attended: she brings the house down.

For those in attendance on this memorable night, among the glittering array of notables who saluted Sondheim, it was the old lady in orthopedic shoes who gets one of the largest ovations of an evening filled with them. The bits of business she was doing sends the audience into hysterics. I listened to Shutta sing this song over and over for years, trying to recall what she did when I saw her do it the one time I saw Follies, but specifics stayed elusive in my memory.

In 1975, while at Purchase College, I was directed in a play by her son, Charles Olsen. I can’t recall how in the days before the internet I came to discover his mother was Ethel Shutta, but of course, once I did, I couldn't help myself from referring to him as “a Broadway Baby’s Baby," as well as pepper him with questions of his mother's career, one of which was "Were you at the Sondheim Tribute?” And when he smiled and nodded yes, I asked “What the hell was she doing?” And he smiled and said, “Everything she’d learned her whole career.”

And now, thanks to YouTube, you can see what it was I tried to recall all those years by way of this mix some kind fan put together with elements from a dress rehearsal at the Shubert Theatre in Los Angeles in 1972 along with footage taken from the wings during Follies' Broadway run (the audio is supplied from a live performance and not the show’s truncated original cast recording, so you get to hear what the insane audience response is about). It showcases something that can’t be taught anymore, especially with no one alive to pass on the secrets of vaudeville. What Shutta does is organic and completely original. Check out what she does on the words “greasy spoon" at the 4:28 mark, but quickly, as it’s so subtle you may miss it the first time around. And watch her bring it home at the end when she is joined by Charles Welch, Marcie Stringer and Fifty D'Orsay to finish out the number. Personally, I can never get enough of her movements — once called “eccentric dancing.” I could watch this footage forever.

Ethel Shutta died three years after this performance at the age of seventy-nine. In show biz parlance, she went out on a high.

If you enjoy these columns, check out Up in the Cheap Seats: A Historical Memoir of Broadway, available at Amazon.com in hardcover, softcover and e-book. And please feel free to email me with comments or questions at Ron@ronfassler.org.

Write a comment ...