October 24, 2024: Theatre Yesterday and Today, by Ron Fassler

In 1982, when John Pielmeier’s Agnes of God was trying out in Boston, the top billing went to Lee Remick, whose beauty and magnetism often obscured her tremendous talents as an actress. A longtime fan of her work, she captivated me from the time I was a child, watching her on TV every chance I could get. For anyone in need of a primer course on what made Remick such an exciting screen presence, look no further than A Face in the Crowd (1957). In a memorable screen debut at age twenty-one, director Elia Kazan plucked her from obscurity to play Betty Lou Feckum, a teenager seduced and abandoned by the frightening Lonesome Rhodes (Andy Griffith). Two years later, she went toe-to-toe in Anatomy of a Murder (1959) with James Stewart, George C. Scott, and Ben Gazzara. Not only do these films remain riveting after so many years, but the way she shines in them brings color to black and white photography.

Her Broadway debut came just after turning eighteen in a short-lived play appropriately titled Be Your Age. A dozen years later, she was a full-fledged star cast alongside Angela Lansbury in Arthur Laurents and Stephen Sondheim’s Anyone Can Whistle (1964) in which Remick introduced the title song. She followed that with a complete change of pace as a blind woman in Wait Until Dark (1966), Frederick Knott’s thriller, later made into the hit film with Audrey Hepburn. The victim of a home invasion (the heroine is inadvertently in the possession of a doll filled with heroin), its climax had people standing up and screaming.

It also bears mentioning for Broadway fans that Remick and Stephen Sondheim shared a deep friendship (they met on Anyone Can Whistle and Remick played Phyllis in the all-star Follies concert at Lincoln Center in 1985). On December 11, 1966, they appeared together on the game show Password (it's special nighttime edition). You can watch it in its entirety here and enjoy their mutual affection for one another, clear as day.

The fact that the password here is “parade” won't be lost on Anyone Can Whistle fans, nor the title of this column "Flaming Agnes," for those Broadway afficiandos who love a good inside joke.

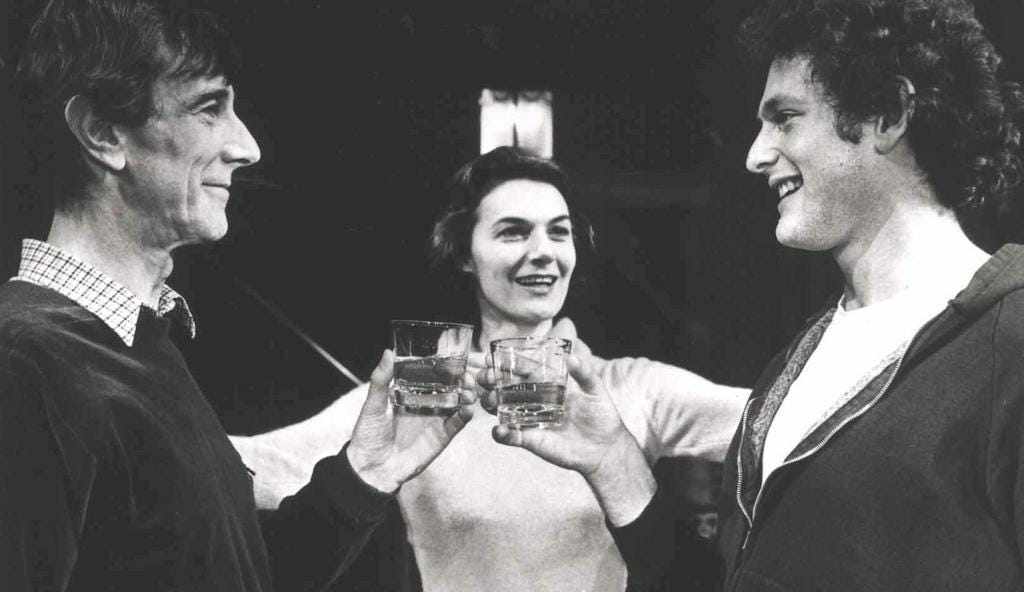

Throughout the late 1960s and ’70s, Remick made numerous films and TV movies that kept her from returning to the New York stage for sixteen years. Broadway beckoned in 1982 with Agnes of God, based on a true event that happened in a Buffalo convent in the 1970s, where a nun (Amanda Plummer) bears a child claiming not to have been pregnant. With the child dead, she is suspected of murdering the baby, leading to bringing in a court-appointed psychiatrist (Remick). Not only does the doctor have to do battle with a reluctant patient, but also a recalcitrant mother superior (Geraldine Page), who is her match in brainy banter. Kevin Kelly of the Boston Globe described the play as “what happens when Equus canters over to a convent.”

Towards the end of its final week in Boston, prior to its Broadway opening, came the abrupt announcement that Remick would be leaving and replaced by Elizabeth Ashley. Reporting on her departure in the Globe, Kelly wrote, “it was obvious she was having trouble with the role.” “Backstage warfare” is also mentioned in the article.

Feels like a little piling up on my beloved Lee.

The old “artistic differences” was the official reason given with nothing further forthcoming. I was privy to a little inside information when, shortly after Agnes of God opened in New York, I audited an acting class that Geraldine Page was teaching. At one point, she was talking about various issues that can arise onstage with a scene partner and shared a story with the class. “I was doing a play recently in Boston with an actress who would not break out from behind her mask,” Page said. “It was infuriating. She held a general smile all night that indicated nothing going on underneath.”

More than forty years later, I got more of the story from the show’s producer, Kenneth Waissman: “We needed three tour de force actors to make Agnes work in addition to them being ensemble players,” he told me. “And Lee wasn’t giving anything. The director, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, kept saying ‘I’ll get it out of her, that’s my job.’ Only when we were entering the beginning of the third week of our four-week Boston engagement, we knew we were in trouble with her.”

Waissman laid out his case for firing Remick at an early morning breakfast meeting with the playwright and the director, only to be met with resistance. Once again, Lindsay-Hogg insisted he could draw the performance out of Remick, but Waissman was unconvinced. He sent for Ashley, who flew to Boston on Friday night. She hid behind dark glasses in the hope no one would recognize her and report that she might be taking over the role.

Upon letting Remick go, Waissman was firm and polite, as he recalled the conversation:

Remick: “Who are you replacing me with?”

Waissman: “That’s not important. What’s important right now is that I’ll speak to your agent. We need to make a settlement and that you have to play the rest of the week and next week.”

Remick: “Well, I don’t know what you’re looking for, but I don’t think you’re going to find it. Because the part is really just someone at the center of a minstrel show, bringing on the acts from left and right.”

At that point Waissman looked over at the director who was slack-jawed that this was all Remick thought of the psychiatrist’s function in the complicated three-person play.

Matters got sticky when Waissman was informed that Remick had gone to her dressing room on Sunday morning, cleaned it out, and headed for her family home on the Cape. Quitting like that meant any settlement her agents might negotiate for her would be negated. Of course, when her agents heard about what she’d done, they got her to return and she finished out the week, playing the good soldier.

And speaking of soldiering, Ashley was onstage in New York eleven days later for Agnes’s first preview. Opening night was delayed a week in order to give her more time and the critics, though mixed on the play’s merits, were generally taken with its theatricality and the three actresses. It became an audience hit and ran for a year and a half.

A few weeks into its run, Waissman got a note from Lee Remick: “I was in town, and I went to see the show and you were right,” she wrote. “I was totally miscast, I didn’t understand the part, it wasn’t right for me, and Elizabeth Ashley was wonderful.”

Now there’s my Lee, a class act.

In the spring of 1991, Remick was set to play Desiree Armfelt in A Little Night Music in Los Angeles, but was replaced by Lois Nettleton when a relapse of her kidney cancer forced her to withdraw. On April 29, 1991, in one of her final public appearances, she attended a ceremony where she was honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Nine weeks later on July 2, 1991, Lee Remick died. She was fifty-five.

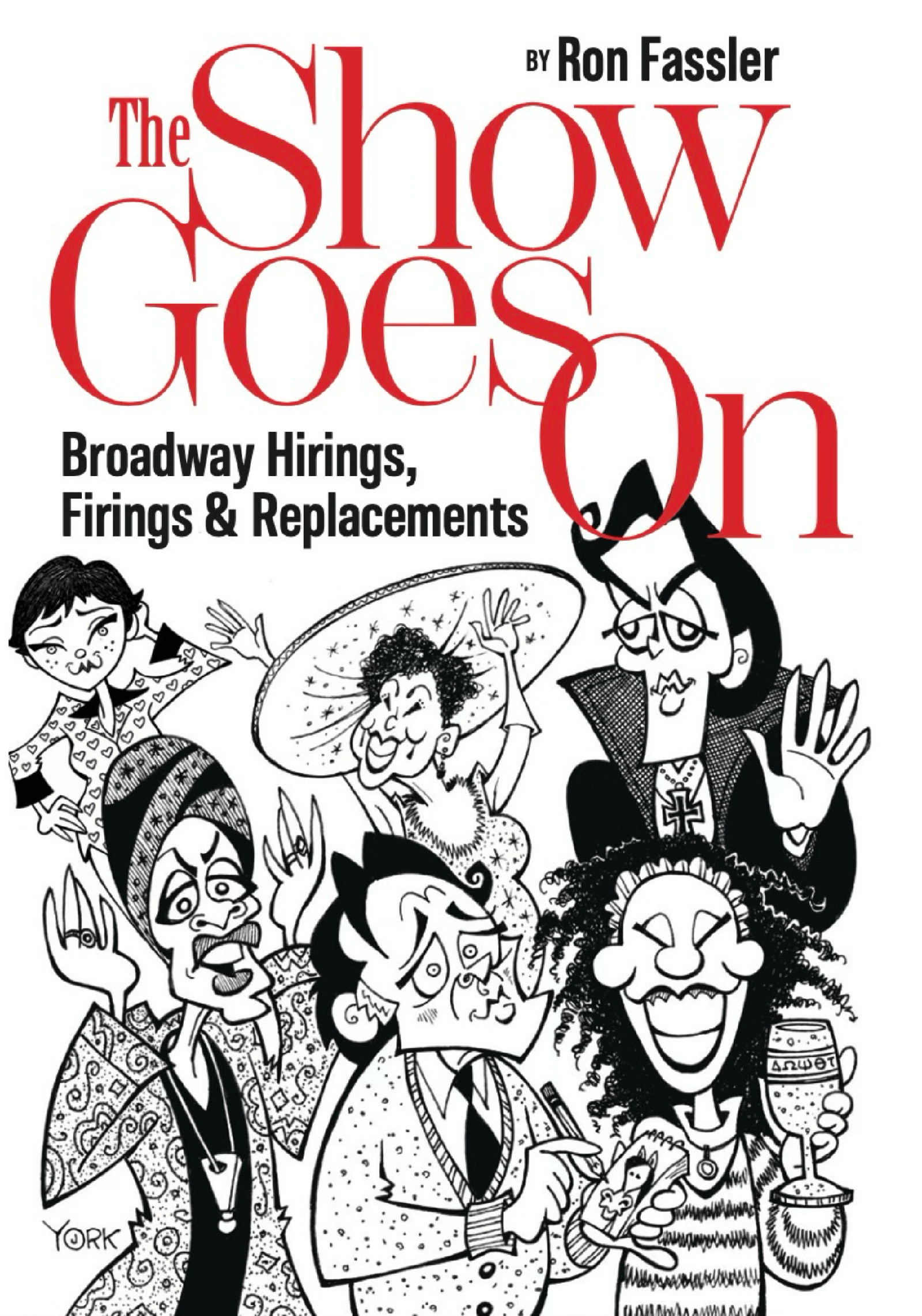

Ron Fassler is the author of Up in the Cheap Seats: An Historical Memoir of Broadway and the forthcoming The Show Goes On: Broadway Hirings, Firings and Replacements. For news and "Theatre Yesterday and Today" columns when they break, please hit the FOLLOW button.

Write a comment ...