October 16, 2024: Theatre Yesterday and Today, by Ron Fassler.

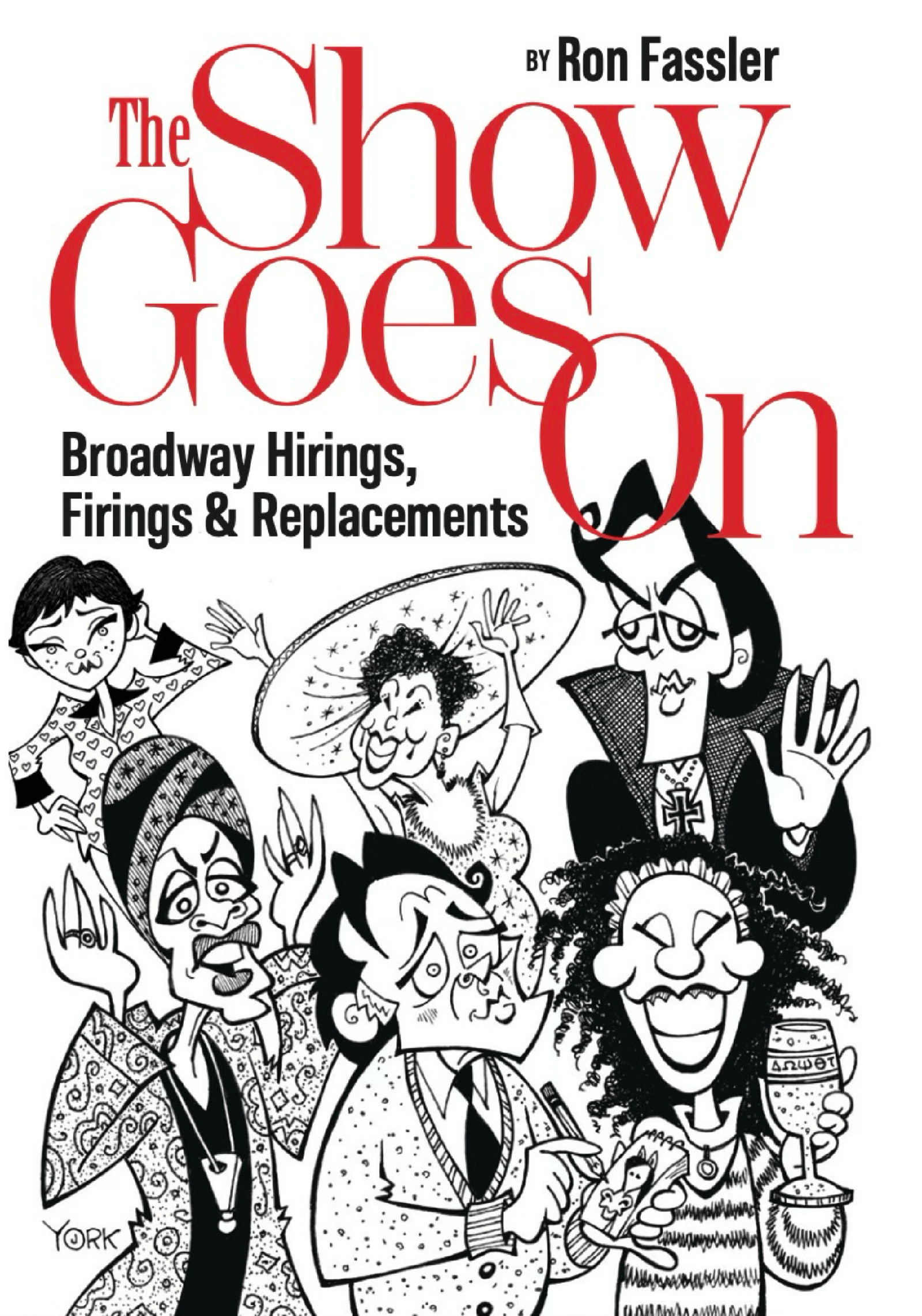

For those with a sense of theatre history and good memories, Michael Bennett’s credits as a stage director extended beyond musicals. Right after Follies, which he co-directed with Harold Prince, Bennett was at the helm of George Furth’s comedy Twigs (1971), in which he guided Sada Thompson to a Tony Award as Best Actress. Two years later, Bennett returned to musicals when he rescued Seesaw during its troubled Detroit out-of-town tryout. That story is the stuff of legend, fully covered in my new book The Show Goes On: Broadway Hirings, Firings and Replacements, available in mid-November. End of plug.

After Seesaw, Bennett was back to a straight play, Herb Gardner’s Thieves, which opened in its Boston tryout in February 1974. It starred Valerie Harper, then famous as Rhoda Morgenstern on CBS’s The Mary Tyler Moore Show. Bennett and Harper had some history together as they had both been in the chorus of the Jule Styne-Betty Comden-Adolph Green musical Subways Are for Sleeping (1961) when Bennett was eighteen and Harper twenty-two.

Harper was only set to play in Thieves for three months on Broadway before returning to Los Angeles to star in her spin-off series, Rhoda. The Thieves producers were counting on good reviews that would easily attract another star of sufficient name value to replace Harper.

The replacing came much sooner than expected.

After it opened to disastrous reviews, Harper walked off the show three days later. Her understudy Susan Browning, nominated for a Tony three years earlier for her performance as the flight attendant April in Company (with Bennett its choreographer), went on for Harper until the producers could figure out their next move.

Marlo Thomas, then playwright Gardner’s girlfriend, had achieved fame in the 1960s with her sitcom That Girl which ran for five seasons. She was the daughter of Danny Thomas, a famous mover and shaker in Hollywood, who had not only starred in his own hit series, Make Room for Daddy, but produced his daughter’s show as well as such classics as The Dick Van Dyke Show and The Andy Griffith Show. When Gardner phoned Thomas on the West Coast to tell her that Harper was out, she got on the next plane to Boston.

When she arrived, she launched into rehearsals and learned the show in five days.

“It’s the gutsiest thing I’ve ever seen an actress do,” said Thieves’ co-producer Gene Wolsk. “This is not the way for an actress of Marlo Thomas’s stature to make her Broadway debut. She deserves three weeks of rehearsal, seven weeks on the road and a couple of weeks in previews, just like everybody else. Thieves was to have opened on Broadway on Thursday. It will now premiere later— if it makes New York at all.”

Wolsk’s fears were realized. He quit the show a few days later, taking his co-producer Emanuel Azenberg with him after Michael Bennett upped and quit. A closing notice went up as well as a sign hung on the glass doors of the Broadhurst where the show was set to open on West 44th Street that read, “Thieves has closed in Boston.”

Time for Herb Gardner to make another call. He rang up Charles Grodin, his friend of twenty years who flew to Boston and caught the show during the period when Browning was performing it and Thomas was in rehearsal. As Grodin says in his written introduction to the play, “After the performance, I told Herb and Marlo and the producers that I didn’t know how good I could help make it, but I knew how to make it better than it was.” He proved all-in to save the day, even taking on the producing reins following Wolsk and Azenberg’s departures. That’s real friendship.

But Grodin faced an uphill climb: the play was weak. Gardner conceived a farcical comedy about a couple involved in a domestic crisis, looking down from their high-rise on the Upper East Side at the various nut-jobs surrounding them on Peter Larkin’s multi-level set. All well and good but Neil Simon got there first with the similarly themed Prisoner of Second Avenue, which had only recently closed after a successful two-year run. Thieves may have gotten a little better with all the changes that were put into it but not being all that great to start with wasn’t enough to stave off critical brickbats.

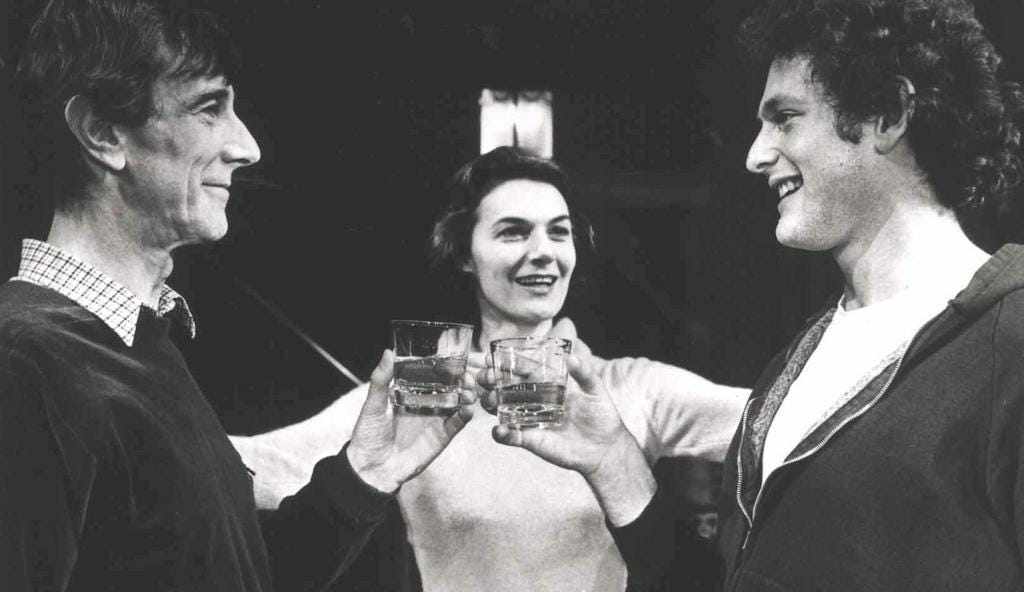

After its mixed to poor reviews (“mawkish and ill-constructed,” wrote Douglas Watt in the New York Daily News), a closing notice went up. Marlo Thomas reportedly tore it down and informed the company every effort would be made to keep the show open. With the creatives taking royalty cuts and Thomas working diligently to finagle every bit of free publicity she could muster, Thieves managed to run for eight months, though closing at a loss of $250,000 on a $350,000 investment. Paramount Pictures, having been a key investor, tried to recover its money by turning it into a film in 1977. Thomas recreated her role with Charles Grodin as her husband, though not directing this time around. Whatever the problems were with John Berry as director, he only lasted five weeks until being fired and replaced by Alfred Viola (Berry retaining screen credit). The film opened and then vanished like a thief in the night but one good thing came out of it: while doing the press tour, Thomas went on Phil Donahue’s eponymous talk show. Their instant attraction grew into a relationship, culminating in a 1980 wedding that lasted up until his death earlier this year.

In a funny replacement story that occurred early in its theatrical run, William Hickey, the actor playing “Street Man” was out sick with no understudy yet assigned. Grodin took to the stage himself, raiding his own closet for the worst of his wardrobe. When the curtain rose, there he was, lying in the gutter. He later said, “Thanks to my friend Herb, I’d become a bum on Broadway.”

While Thieves was still struggling along in its eighth month, Neil Simon brought in a new comedy, God’s Favorite, directed by Michael Bennett. A misguided comedic update of the Job story from that old bestseller The Bible, it featured Charles Nelson Reilly as a messenger from God named Sidney. Limping along for 119 performances, it proved Bennett's final foray into the world of plays without songs. For his next show, he decided to set it behind the scenes of a new musical that wouldn’t be about the stars and the creators, but instead focus solely on a group of random dancers who are the finalists at an audition: the kids in a chorus line hoping to get it. The rest, as they say, is history.

Ron Fassler is also the author of Up in the Cheap Seats: An Historical Memoir of Broadway. For all future "Theatre Yesterday and Today" columns, hit the FOLLOW button.

Write a comment ...